Three Views of Bamako

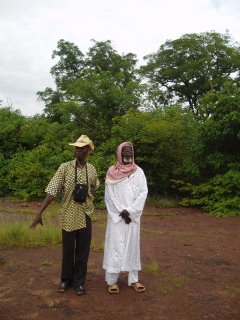

This past Sunday, after the usual breakfast of French bread and tea, my classmate, India, and I walked up to the top of the nearby hill that serves as the backdrop from our balcony view. It was a leisurely afternoon stroll, an exploration of one’s backyard. We live on the edge of town and are relieved from the pollution and noise that plague most of Bamako. Still, like most neighborhoods with cement buildings and open courtyards, we’re used to a certain amount of sound. So we were amazed at how quickly the city hushed as we followed the thin trail through knee-high grasses.

We stumbled upon a few farmers, terracing the steep hill, but mostly it was just us and the grasshoppers, dragonflies, and lizards. From the very top, all of Bamako sprawled out in front of us, with the Niger River in the distance and the one skyscraper (a bank) barely protruding above the horizon. Sometimes I feel like I’m exploring Mali through someone else’s eyes, like I’m in the Matrix or in The Truman Show; I guess the landscape is so foreign that I’m having a difficult time grasping it. I think one reason is that nothing is more than two stories tall and my concept of perspective and depth perception is somewhat skewed. Looking out over the city, my neighborhood looked impossibly close, like a model train set, and then suddenly everything else seems very far away.

Later that evening, I ended up on our roof, flat like all the houses in Bamako. I had spied lightning in the distance and wanted to watch the storms roll across the city, bringing a much needed, if only brief, relief to the heat and humidity.

Bamako’s population of one million citizens does not cast the same amount of light pollution as comparable cities in America; rather, the indications of nocturnal human activity are limited to fluorescent pinpoints of courtyard lights and an occasional yellow glow, spinning around in tiny circles. This latter phenomenon is the result of a tea making practice here in Mali. A small kettle is balanced on an outdoor stove that is stoked with bits of charcoal. In order to accelerate the heat and flames, the stove is gripped and whipped around in large arm circles. The effect at night is always unexpectedly magical, somewhat like fireflies in the summer.

As I sat on some scrap wood, I couldn’t hear any thunder, just the murmurings of Djoumanzana (our district in Bamako). Crying babies, moped motors, radios, a far off dance-party, and drawn-out calls from the mosques loudspeakers, reminding Muslims to pray. The rain didn’t arrive until hours later, but for a short time, I was content enough, alone on the roof.

Every city has a pulse, an internal rhythm of its inhabitants as they move about their daily activities. For example, Seattle has its brisk caffeinated clip that is contra posed by a steady early morning rain. Bamako, when viewed from my earlier vantages looked vast and quiet. Standing in the heart of downtown, however, is to be surrounded by a frenzied beat, a whirling of human noise, bright colors, and the pollution-induced coughs.

Recently, we were sent to explore the city in small groups equipped only with our limited language skills and a map that was drawn by a blind kid during the minimalism art movement. Because street signs are nonexistent, we eventually abandoned our “map” and resorted to just asking random pedestrians. Even though we could barely understand their directions, their vague hand gestures were enough to tell us if were headed in the right direction (their laughter told us when we were completely lost). We quickly learned that it was inappropriate to just flat-out ask “Ou est l’embassade d’Etats-Unis?” (Where is the American Embassy?). Malian society has an extensive greeting protocol and at the very least, a “Bonjour, ca va?” (Hello, how are you?) must precede any other questions.

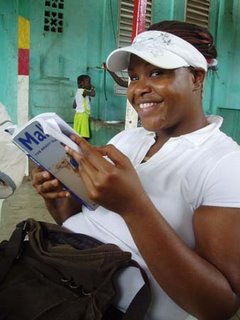

Children are very confident about just walking up and demanding a handshake with this greeting; adults on the other hand that approach us out the blue deserve a bit more hesitation. “My brother, my friend, how are you?” they cajole before displaying their wares for sale. They’ll go so far as thrust a too-small ring on your finger so that once stuck in place, you’re forced to purchase this new jewelry. The trickiest are the ones that offer a helping hand, accompanying us to our destination or calling a taxi, and then demanding payment for their unadvertised services. Sometimes I feel cold-hearted as I walk quickly by these hustlers and my more compassionate classmates pause to politely listen. Then again, I’ve still got money after these interactions.

Bamako is intense and over-stimulates every sense. Masses of human bodies, wrapped in bold colors and patterns, crowd the narrow sidewalks. Cars, mopeds and vaches (van-like public transportation that costs about 30 cents) rush down roads that lack lane markers and stop lights. Their high-pitched honks are cute but their exhaust fumes are debilitating. Whenever we return from the city, we’ve all contracted emphysema and produce mucus that looks like we’ve been working as coal miners. The smell of the city was one of the first things I noticed when I disembarked our plane: like burnt plastic, but more earthy. From the market stalls, roasted peanuts, sizzling goat meat, sun-baked fish, and open sewers add to this olfactory canvas. Your arms are sweaty and stick a millisecond too long whenever your brush against other shoppers. Your feet are hot and dry from all the dust and looks well tanned until you realize it’s just the dirt. This is a place of constant movement, where standing still is not recommended unless you mean to attract a group of suspiciously gregarious men. Our French teacher, Isabelle, applauded us are we returned home an hour late, as if we were weary soldiers, dragging ourselves from the frontlines of a war zone.

Honestly, as much as I love going into the city, it is an exhausting experience. We’ll be in homestays for the month of November and I’m not sure if I can handle a month of living downtown. However, I’m also recognizing the exponential rate at which we are adapting to our new environment. I’ve reached the point in this semester where I’m realizing that it’s not just a weeklong trip, that it will be easier to embrace my environment rather than hide from it in my bedroom with a CD player and magazine. Yes the city is beautiful when viewed from afar, but there’s only so much time you can spend on a roof before you need to get down and walk in its streets. At some point, you have to stop listening to a city’s beats and start playing them.